The ups and downs of inter-country adoption

- A Family for Every Child: International Adoption of American Children in the Netherlands

- Adoption options plummet as Russia closes its doors

- Brazil - misc trafficking cases

- China probes child trafficking, adoption link

- Committee on Enforced Disappearances Marks First Anniversary of the Joint Statement on Illegal Intercountry Adoptions

- El Salvador - Children stolen during Civil War case

- Foreign adoptions by Americans plunge again

- International Adoption: Two Way Street

- Netherlands limits adoptions of US children

- New regulations make international adoption harder than ever for Americans

Earlier this month, the US Department of State, published its annual report on inter-country adoption, and for the 10th year in succession, the number of children adopted from abroad dropped.

Much has been written in the last decade, about this decrease in inter-country adoption, and while it is a real phenomenon that can be observed in all receiving countries, there is more to the story than just a decline within the last decade.

When American mainstream media reports news about the decline in inter-country adoption, they usually use 2004 as a starting point, when the US alone received 22,972 children from abroad.

Any recent figure will pale in comparison to this figure. For instance, the 6,441 children adopted from abroad in 2014 is less than one third of the number reached in 2004.

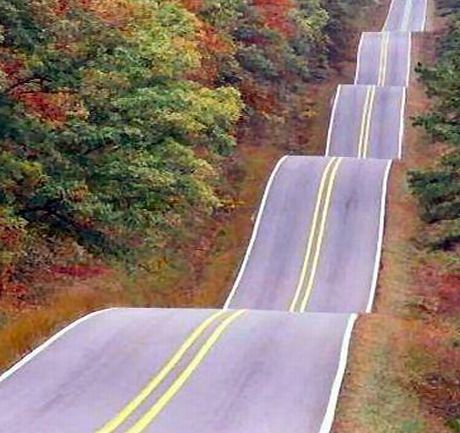

Articles about the decline in inter-country adoption are often accompanied by graphs like the following, demonstrating the free fall of the number of adoptions from abroad over the last ten years.

Graphs are a great tool to visualize otherwise impenetrable time series, but they can easily hide as much as they show. The usual graphs of the decline in inter-country never show the period before 2004.

If we present a graph of the time period 1992-2014, we get a very different picture.There still is the rapid decline since 2004, but it now becomes clear there was an almost as rapid increase of inter-country adoption before the high-watermark of 2004.

Most of the increase in inter-country adoption between 1995 and 2004 can be ascribed to the entrance of China and the former Eastern bloc to the inter-country adoption market. As a result, large numbers of children became available for inter-country adoption.

Not only was the supply of adoptable children growing, the demand for children grew, as well. It was during the 1990s when reports came out about the deplorable situations in many children's homes in Eastern Europe, outraging many who saw adoption as a means to save these children from further harm. Another news-worthy report that affected the number of adoption came through a focus on China's one-child policy, and the consequences forced family-planning brought those who dared to exceed China's pregnancy limits.

These extenuating circumstances during the mid-1990s were not going to last forever. China's economy grew almost 10 fold over the last 20 years, and a middle-class emerged, creating a population capable of absorbing the children in need of placement. Meanwhile, back in Eastern Europe, most countries of the Eastern bloc joined the European Union and saw some steady improvement, both economically and socially. Russian too has improved economically, and the need for foreign assistance, through international adoption, has decreased.. With economical improvement, ICA is no longer the only way to care for Russia's children in averse circumstances.

The decline of inter-country adoption in Russia has created a compounding effect: with a rise of nationalism, an increased assertiveness developed in the international arena. This assertiveness can be seen in the following chart, which shows the percentage distribution of children sent for adoption, per year, to various receiving countries.

While almost all countries saw a decrease of adoptions from Russia since 2004, the United States saw its part of the pie shrink disproportionally ever since 2000.

It can be argued that the relative decline of adoptions by the US from Russia before 2004 is mostly explained by the rapid rise of adoptions from Russia in Spain and Italy. The US already received large numbers of children from Russia late 1990s and saw that number grow with 36% between 2000 and 2004. Spain, however, saw an increase of 226% in that same period while Italy achieved an increase of 446%.

The relative decline of adoptions from Russia by the United States after 2005 is not as easily explained. There are no new countries starting up adoption programs from Russia, yet there is a disproportionate reduction of children going to the US.

This may be explained by the numbers of children going to Italy. While all countries have seen a decrease of adoptions from Russia since 2004, Italy has more or less flat-lined. The number of children adopted by Italians from Russia in 2013 is almost the same as the number from 2004.

A level of political favoritism cannot be dismissed. Even though President Bush could see the soul in President Putin's eyes, the relationship between the US and Russia has been strained for more than a decade. At the same time President Putin has maintained a close friendship with former Italian Prime Minister Silviu Berlusconi. Whether such favoritism alone explains Italy's exceptional position is probably a Kremlin secret, but it is not inconceivable. Inter-country adoption has demonstrated to be an issue of the highest diplomatic importance at times.

If anything we can learn from looking at the numbers of children adopted from abroad, it is that no singular pattern applies. When we compare the different countries, there are some commonalities during certain periods, but there are also large differences.

To show how similar and how different countries can be, we compare four receiving countries, the Netherlands, the United States of America, Sweden and France. The reason we chose these particular countries lies in the availability of statistical data. Only for these four countries could we find data that spans several decades.

Netherlands 1957-2014

For the Netherlands we have a remarkably complete set of data, going back to 1957, although the data is not broken down per sending country before 1972.

The first 15 years show low levels of inter-country adoption, primarily from European countries. Greece was by far the largest sender. Of the 1,010 children adopted from abroad between 1957 and 1970, 478 were of Greek extraction. Germany, Austria and Belgium were also a source of adoptable children during this period, as was Lebanon.

In the 1970s an explosion of inter-country adoption took place, which reached its peak in 1980 at a level never seen since. Like the previous period, adoptions from Europe still played a role, but phased out near the end of the decade.

During this period, even a few children were adopted from Eastern Europe. Four children were taken from Hungary, three from Poland and one from Romania. Another 131 were adopted from Yugoslavia during the 1970s. Also noteworthy was that fact that six children were adopted from China during this period, as well as six children from Ethiopia, 15 from Guatemala and 18 from the United States.

The largest contribution to the rise of inter-country adoption in the Netherlands in the 1970s, however came from Asia. Two-third of the children during this period came from Asian countries, predominantly from South Korea (2,317 children), Indonesia (1,788 children), India, (865 children), Bangladesh (486 children), Sri Lanka (158 children), Thailand (90 children), and the Philipines (34 children). With 335 children, Lebanon still played a role during this period too.

In 1975, nine children transported from Vietnam during Operation Baby Lift were sent to the Netherlands, while another 66 children reached the Netherlands through other means.

South America was another important source of children, Colombia being by far the largest, sending 979 children to the Netherlands. Programs were also started in Peru (112 children), Brazil (110 children), Chile (106 children).

The 1980s showed a steady decline of inter-country adoption in the Netherlands. Adoption from Indonesia halted in 1983, which contributed largely to the decline, but also adoptions from South Korea falled down dramatically during this period.

India, Colombia and Sri Lanka made up for some of the losses during the 1980s and explain the spikes in some of the years. Especially the program in Sri Lanka was hugely popular in the 1980s, peaking at 565 children in 1986. After that, a steady decline set in, but the program exists to this day.

Adoption from Europe during this period started to shift from Western European countries to Eastern European countries. In 1983 the last children from Germany and Austria were adopted, while 70 children from Poland were adopted by Dutch parents as well as 12 children from Hungary.

The only African country of note during the 1990s was Ethiopia, with 90 children during that decade, the largest sending African country.

The most notable shift during the 1980s however was one from Asia to South America. While Asia remained the largest supplier of adoptable children during the 1980s, South American adoptions actually grew, Colombia and Brazil being the largest suppliers. During this period adoptions from Chile and Peru phased out, while adoptions from Haiti started up.

The decline of adoption during the 1980s was not just a question of a reduction of supply, but also of demand. Economically, the Netherlands was doing worse than during the previous decade, with relatively high levels of unemployment. Prospective adoptive parents also shied away when the first research reports into inter-country adoption showed the children could have serious developmental issues. The first stories of child trafficking emerged and were picked up by the news media in the Netherlands. These factors likely contributed to a lower level of interest in inter-country adoption.

The 1990s started with two short-lived spikes, predominantly caused by equally short-lived increases in adoptions from Sri Lanka, but it wasn't until 1998 that adoption in the Netherlands started to increase again. This increase was almost entirely the result of adoptions from China, which rose from 26 children in 1992 to 457 children in 2000.

Europe remained a minor contributor during the 1990s and all children came from Eastern Europe: Poland (251 children), Romania (184 children), Bulgaria (31 children). Interestingly, no children from Russia were adopted in the Netherlands.

The only notable country in Africa remained Ethiopia which sent 460 children to the Netherlands during the 1990s.

Colombia (1,686 children), Brazil (660 children) and Haiti (254 children) remained the dominant suppliers from the Americas during that period, although Guatemala, which had been a minor but steady supplier of children since the 1970s, saw a sudden surge near the end of the 1990s.

After a hiatus of almost a decade, adoptions from the US also continued during this period. The numbers were still low (47 children)

Asia, however, was by far the largest supplier of children during the 1990s. China placed 1417 children during this period. India, while sending fewer children than during the 1980s, still placed 617 with Dutch parents.

Taiwan saw a significant increase too. The country had been sending very small number of children since 1975, but during the 1990s that number rose to 371. South Korea also made a comeback. Where that country sent almost an almost negligible number of children at the end of the 1980s, it managed to send 371 children throughout the 1990s.

The increase of adoptions from Taiwan and South Korea were interesting and probably show a change in attitude. Inter-country adoption in the 1970s and early 1980s had mostly been idealistic, with many children coming from poverty stricken areas. In the mid 1980s, this shifted to countries that were more likely to send healthy infants, irrespective of humanitarian needs.

The 2000s saw a further reliance on China for the supply of adoptable children. During this decade, almost half of all adoptable children came from China (4603 children). After the number of children from China peaked in 2004, another decline of inter-country adoption in the Netherlands started.

It is not just China that showed a decline during this period. Colombia, one of the most reliable sources of children, since the mid-1970s started sending fewer and fewer children. Colombia sent 978 children during the 2000s, but by the end of the decade adoptions from that country had been reduced to only a handful of children each year.

India (206 children). Brazil (159 children), South Korea (105 children) and Guatemala (62 children), too sent ever fewer children, and by the end of the decade, adoptions from those countries had effectively stopped.

The only countries that saw some increase during the 2000s are Haiti (643 children), Ethiopia (504 children), Taiwan (474 children) and the United States (312 children).

The overall numbers of inter-country adoption in the Netherlands have dropped to levels found when inter-country adoption started to boom in the early 1970s. There are some new programs from Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya and South Africa, which all started in the 2000s and have been flat-lining over the last couple of years.

For the last 40 years, the Netherlands has mostly relied on programs that were started during the 1970s. The only exceptions are Haiti, which started sending children in the 1980s and China, starting in the 1990s.

Until the early 2000s, there was a solid baseline of 600 inter-country adoptions per year from various programs. Anything in excess of that number, depended largely on one or two over-performing programs. With the decline of most traditional programs, inter-country adoption in the Netherlands has become an almost negligible phenomenon.

United States of America 1962-2014

For the United States we have less detailed figures than for the Netherlands, so we can't give as comprehensive a narrative of the ups and downs of the inter-country adoption numbers, but despite that lack of detail we can still tell at least part of the story.

Although adoption from South Korea started much earlier in the United States than anywhere else in the world, its influence on the numbers for the 1960s shouldn't be overstated. Throughout that period, the percentage of adoptions from South Korea was in the order of 30%. Other sending countries in that era were Germany, Austria, Greece and Canada, although exact figures are unavailable.

The 1970s saw a rapid increase of inter-country adoption in the US. An explosion of adoptions from South Korea was by far the most dominant factor. In 1976 alone, South Korea sent 4008 children to the US, while the total number of inter-country adoptions for that year was 6,552.

Notable during the mid-1970s were adoptions from Vietnam, as part of Operation Baby Lift, which brought 1,697 children to the US. After that initial surge, it would take until the 1990s before Vietnam became a serious exporter of children again.

After 1977 the number of adoptions from South Korea declined, although that loss was somewhat compensated by an increase of adoption from other countries. Exactly from which countries children were adopted during that period is not in our data set, but it's likely they include Colombia, the Philippines, India, Thailand, Guatemala and Mexico.

In 1982 the number of adoptions from South Korea started to rise again, reaching an all time high of 6,138 children, in 1986. During those four years, South Korea was again the dominant sending country, making up almost two-thirds of all inter-country adoptions to the United States.

After 1987, the year before the Olympics in Seoul, the number of adoptions from South Korea declined fast until 1991, when 1,818 children from South Korea were adopted by US adopters. That level remained fairly stable until 2005.

Between 1987 and 1992, the number of inter-country adoptions in the US declined considerable, with a singular exception in 1991, when 2,751 children from Romania were adopted as a result of an adoption mania after the fall of the Ceausescu regime.

In 1992, Russia started sending the first children to the US. The same year, China started expanding inter-country adoption as well. In the following years the number of adoptions from Russia and China grew exponentially. Already in 1998, both countries sent more than 4,000 children each to the United States. Russia reached its maximum in 2004, when it sent 5,862 children, while China peaked a year later, with 7,903 children sent to US.

The former Soviet republics Ukraine and Kazakhstan also saw the number of adoptions in the US grow significantly during the 1990s. Ukraine peaked at 1,240 children, in 2001, and Kazakhstan peaked at 835, in 2004.

Further compounding to the rise of adoption in the late 1990s, were Vietnam and Cambodia. Programs from both countries were rife with corruption and only lasted for a couple of years, although the Vietnamese program restarted in 2006, to be closed down again in 2009.

The late 1990s also saw the rise of adoptions from Guatemala. Until 1997, the numbers had been in the order of 400 children per year, but then started to surge, reaching a maximum of 4,726 children, in 2007.

Finally Ethiopia followed with an unsustainable expansion. from 165 children in 2003, to 2,511 children in 2011.

In 2014, the numbers of all adoption power houses were much lower than in the previous two decades. China was the only country that still sent a significant number of children to the US, although the numbers were only one fourth of what they were a decade earlier. Russia halted adoptions to the US altogether and sent only 2 children in 2014. Guatemala was no longer a player, with 29 children in 2014, and even Ethiopia's numbers dropped to 716 children in 2014.

South Korea, once the mainstay of America's inter-country adoptions sent 370 children in 2014. This was an uptick from the year before, when only 138 children were sent for adoption, but it was still far below the numbers that were sent in previous decades.

Other traditional sending countries like India, Colombia and the Philippines showed declining numbers as well, in 2014.

The only countries that have seen considerable growth in the previous years are Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Ghana and Nigeria.

Inter-country adoption in the United States over the last 40 years has shown a strong dependency on a very small number of countries that sent large numbers of children.

In the US, there has been a solid baseline of some 3,000 inter-country adoptions per year over the last four decades, from a variety of countries. The numbers in excess of that baseline, have mostly been due to a small number of countries, sending huge numbers of children.

Due to the large number of adoption agencies in the US that collectively cover almost all sending countries, the baseline is not likely to be influenced all that much, When some country starts sending large numbers of children again, the US will be the first recipient.

Sweden 1969-2014

For Sweden, the data we have is a mixed bag of goods. We have absolute numbers since 1969. We have monthly figures for one agency (Adoptionscentrum), since 1975. We have yearly figures for another agency (Barnen framför allt ) since 1980. And we have the total number of children adopted from South Korea since 1958. Although the picture we have is far from complete, there nevertheless is an interesting story to tell.

In 1969, the first year we have data for, Sweden already received 1,031 children from abroad, of which 198 from South Korea. This is a staggering amount when we realize that the United States received 2,080 children that same year.

We know very little about the countries Sweden received children from early on, although we can expect Germany, Austria and Greece to be likely candidates.

Adoptions from South Korea quickly grew during the first years of the 1970s and peaked at 636 children in 1974. By that time, there were also established programs from India, Chile, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Colombia, Indonesia, Guatemala, and a handful of other countries that sent small numbers of children and wouldn't play a major part in later years.

During the 1970s, Chile was one of the major sending countries for Sweden, reaching its peak in 1978 and then slowly declined, until adoption from Chile stopped by the early 1990s.

After the peak of inter-country adoption in 1977, Sweden basically settled on three programs: South Korea, India and Colombia. South Korea settled at a level of around 300 children each year, until 1988 and then settled at a level of around 100 children for the next 20 years. India saw the number of children sent to Sweden grow to a peak of 273 in 1983, after which a slow decline set in. Colombia peaked in 1985, that year sending 322 children to Sweden, and then set in a slow but steady decline.

In 1991 and 1992, inter-country adoptions to Sweden had a short-lived peak. This peak can partially be explained by several programs doing slightly better those two years, but we also expect adoptions from Romania to play a part in that particular peak.

In the 1990s Vietnam started playing a role in Swedish adoptions. The country had mostly been dormant after Sweden had received sixteen children during Operation Baby Lift. The numbers went a bit up and down through the 1990s, but reached a clear peak around 1999, after which the numbers started to drop. Russia too started sending children from 1990 onwards, peaking in 1998 after which a gradual decline set in.

The sole reason, inter-country adoption rebound somewhat in the late 1990s has to do with China. The number of children from that country grew quickly to a peak of 497 in 2004, after which the numbers fell as quickly as they had risen in the years before.

These days inter-country adoption in Sweden is marginal. The numbers are one third of what they were in 1969. The only countries that have shown some growth over the last couple of years are Taiwan and Kenya, but the numbers are too low to have an impact.

Sweden's baseline remained more or less stable until the mid-1980s at around 1,300 inter-country adoptions per year, based on only a handful of programs. Once those programs started to decline, inter-country adoption in Sweden collapsed. Adoptions from China temporarily raised the numbers in the early 2000s, but once those numbers started to drop, inter-country adoption in Sweden became a negligible phenomenon.

France 1980-2014

The data we have for France is fairly limited. We have the total numbers per year since 1980. We have the number of adoptions from South Korea since 1968. We know 205 children transported from Vietnam during Operation Baby Lift were sent to France, in 1975, and we have detailed numbers broken down per sending country since 2000. As a result the story we can tell is relatively minimal.

In 1980, France relied for more than half its inter-country adoption program on South Korea. Adoptions from that country had steadily grown from the first children in 1968, until its peak in 1985, when 975 children from South Korea were adopted in France.

The increase of inter-country adoption in France in the early 1980s however, can not be explained by the growth of adoption from South Korea alone. Some other programs must have contributed to the growth too. We have no information, but expect based on later data that Colombia, India, Thailand, Brazil, Madagascar and Haiti were among the contributing parties.

The spike of 1990 and 1991 is probably the result of the adoption mania surrounding Romania, with France being one of the main forces behind that mania and as a result one of the main recipients of children.

In 2000, Romania was the largest sending country for France, exporting 370 children that year, but those numbers quickly dropped and were already negligible two years later. Since 2006, France has not received any children from Romania.

The rise of inter-country adoption in France between 2000 and 2005 is more complex than for most other countries. Adoptions from Russia played a role, showing an increase of 341 children. Adoptions from China played a role, showing an increase of 353 children, but adoptions from Vietnam played an even larger role, showing an increase of 783 children, and adoptions from Haiti also show an increase of 404 children.

Those increases were offset by decreases from countries like Romania, Cambodia, Guatemala and Bulgaria. These four countries may have been responsible for the peak of inter-country adoption between 1996 and 1999, but we have no data to back that up

The sudden drop in 2007 can almost entirely be explained by a decrease of the number of adoptions from Vietnam. Those numbers veered back up until 2011 and then started to decline again. The spike of 2010 has mostly to do with Haiti, which sent 992 children that year, but those numbers collapsed completely the year after.

Madagascar played a minor role in the decrease after 2006 when that program collapsed, and also Ethiopia contributed to the general malaise in recent years by dropping from 484 children in 2008, to 52 in 2014.

Nowadays, the number of adoptions in France are as low as they were in the early 1980s, almost 3,000 lower than during the peak of the first half of the 2000. Given the make-up of the French adoption programs it is not unlikely that the numbers will start to grow again. Adoptions from Haiti may pick up and so may the adoptions from Vietnam, but the levels seen a decade ago are unlikely to be attained in the near future.

In contrast to the Netherlands and Sweden, France has a broader base of programs. It has not relied for decades upon the same handful of sending countries, but instead placed a significant number of children from various countries. As a result the general decline of traditional sending countries like South Korea, Colombia and India has had a lesser impact on inter-country adoption in France, than in other countries The collapse of adoptions from Eastern Europe has had a major impact on the French adoption system and is reason to expect a return to the heydays of the 1990s and early 2000s, to be most unlikely.

Other countries

For most other receiving countries we have data broken down per sending country since 2000 and the number of adoptions from South Korea since 1953. A lack of data prevents us from telling much of a story about the development of inter-country adoption, so we will limit ourselves to some observations we can glean from the data we do have. We omit Ireland, Finland, Israel and Iceland, because the numbers are too low to have any significant impact on the total number of inter-country adoptions. We also omit the United Kingdom, Austria, New Zealand, Luxembourg, Slovenia, Malta, Andorra, Monaco, Cyprus and Portugal. We only have partial statistics for those countries since 2000, and the statistics we do have show very low numbers as well.

Canada

Although Canada showed a small, but remarkable uptick of inter-country adoption in 2013, its numbers for 2014 show a further decline that set in in 2003.

Canada has legacy programs from Haiti, the Philippines, India, Thailand and Colombia. Adoptions from South Korea started in 1967 and show an remarkable pattern. With the exception of a small spike in 1976, the numbers remained relatively low throughout the 1970s. In the 1980s the numbers were bit higher but not much, with the exception of 1985 and 1987 when Canada adopted more than 1,100 children from South Korea.

During the 1990s only a handful of Korean children were adopted by Canadians, but those numbers rose again in the 2000s. Canada participated in adoptions from Russia and Romania since the 1990s. It also participated in the program from China, which followed the same pattern as anywhere else.

Canada is by far the largest recipient of children from the United States, having received on average 115 children per year since 2000. With 905 children adopted from abroad in 2014, Canada is one of the larger receiving countries. It has programs in many different countries. As a result, the Canadian adoption system is probably more resilient than that of Sweden or the Netherlands, which have relied on a small number of programs for a long period of time.

Italy

Italy is a remarkable country when it comes to inter-country adoption. Where most other receiving countries saw their numbers peak in 2004, Italy only peaked in 2010.

Although the first adoptions from South Korea took place in 1965, the numbers remained low and only a handful of Korean children were adopted in Italy after 1980.

India is the only Asian country Italy has a long standing relationship with, although there were some bursts of adoption from Cambodia in the mid-2000s, when most other countries had phased out those programs due to corruption. Italy also followed France and the US in an adoption burst from Vietnam in the late 2000s. Those programs too were plagued with corruption. Unlike most other receiving countries Italy started adoptions from China only in 2009, five years after that country reached its peak.

Italy has several programs from South- and Central America, most notably from Colombia, Brazil, and to lesser extent Peru, Chile and Bolivia. While most other countries saw the number of adoptions from these countries decline after 2000, those numbers grew in Italy. Between 2000 and 2011 the number of adoptions in the rest of the world declined at about the same rate they climbed in Italy.

As we already indicated in our introduction, Italy also has a remarkable performance with respect to Russia. Where the numbers dropped significantly in all other receiving countries, the numbers stayed more or less flat in Italy, with a temporal dip in 2007 and 2008.

Italy has been very involved in the adoption of children from Eastern Europe since the early 1990s. It was one of the first countries to receive children from Romania in 1990 and was even able to squeeze out the last 119 children before Romania closed its borders in 2005. It has managed to grow the number of children adopted from Hungary since 2000, although the numbers never got really large,

Major sending countries from Eastern Europe are: Ukraine, Poland, Bulgaria, Belarus, and to a lesser extent in more recent years Lithuania, Latvia, Armenia and Slovakia.

Between 2000 and 2010, Italy more than doubled the number of children adopted internationally, and has only shown a decrease in the last two years. With 2,825 children adopted from abroad, Italy is the second largest receiving country in the world.

Spain

Spain is probably more affected by the decline of inter-country adoption than any other country. At its peak In 2004, Spain was easily the second largest receiving country in the world, adopting 5,538 children from abroad that year. In 2013, those numbers had shrunk to 1,191. Figures for 2014 are not yet available, but there is no reason to expect anything other than a further decline.

Spain arrived late in the game of inter-country adoption. It didn't participate in adoptions from South Korea, with the exception of five children in 1968. It also didn't start programs in Asia and South America in the 1970s, and by 1988 only received 93 children in total.

During the 1990s things changed. Spain became a major recipient of Romanian children, and also sought large numbers of adoptions from Russia, China and Ukraine.

Spain also started adoptions from traditional sending countries like Colombia, India and to a lesser extent Bolivia and Peru, but those programs decreased since 2000, as did the program from Bulgaria.

There were some short lived attempt to expand inter-country adoption through Ethiopia, Nepal, Vietnam and Kazakhstan, but that never resulted in more than short bursts of children after which the programs declined.

Norway

Norway, in 2000 had programs similar to Sweden and the development ever since shows the same patterns. Norway started adoptions from South Korea in 1956, two years before Sweden, but developed at a slower pace.The peaks in the 1970s were not as pronounced and also the decline after 1987 is not as steep. Like Sweden, Norway these days adopts only a handful of children from South Korea.

Legacy programs exist from Colombia, Ethiopia, India, the Philippines and Brazil, with the program from Colombia being the by far the largest. All those programs show a decline since 2000.

The total number of inter-country adoptions in Norway are currently much lower than they were in the early 1970s. 154 children were adopted from abroad in 2013.

Denmark

Denmark too followed much of the same pattern as Sweden. We can see legacy programs from Colombia, India and to a lesser extent from Bolivia and Thailand running to this day, but clearly at a much lower rate than before.

Adoptions from South Korea started in 1965, but only really picked up in the early 1970s. There was a peak of 555 children in 1973, after which it stabilized around 400 children per year until 1987. Since 1987 adoptions from South Korea have declined and are negligible these days.

Unlike Sweden, Denmark had an uptick of adoptions from Ethiopia between 2008 and 2011. The total number of inter-country adoptions in Denmark are these days lower than they were in the early 1970s, with 174 children adopted in 2013.

Belgium

Belgium has legacy programs from Colombia, India, Haiti, Thailand and to a lesser extent the Philippines.

Adoptions from South Korea start in 1968, they peaked in 1975 when 408 children were place. The numbers dropped considerably in 1980, rose back a little until 1987 and then quickly faded out. Belgium virtually ended adoptions from South Korea in the early 1990s.

Adoptions from Ethiopia show an uptick between 2005 and 2011. The total number of inter-country adoptions in Belgium currently is low, with 219 children adopted from abroad in 2013.

Switzerland

Switzerland has legacy programs from Brazil, Colombia, India, Thailand, and to a lesser extent from Haiti, Peru, Bolivia and Chile. The country did participate in adoptions from Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, but at relatively low levels.

Adoptions from China, although existent are negligible. Adoptions from South Korea started in 1968, peaked in 1974, when 228 children were placed. After that peak adoptions from South Korea faded out quickly and at most one or two children per year were sent to Switzerland.

In 2013, inter-country adoptions dropped to a level of 256 children. Most legacy programs have run their course. Ethiopia is now the main source of adoptable children with Morocco being in second place.

Germany

Germany has always been a minor player in inter-country adoption in spite of its large population and wealth. It was mostly a sending country in the 1960s and early 1970s, although it did receive children from South Korea as early as 1965. Those adoptions peaked in 1976 when 194 children were placed with Germans. Again we see the numbers stabilize at a lower level until 1987 and then fade until adoptions from South Korea virtually halted in the early 1990s.

There are legacy programs from Thailand, Colombia, India, Brazil,. the Philippines, and to a lesser extent from Sri Lanka, Bolivia, Peru and Chile.

Germany did place children from Russia, Romania, Bulgaria and Poland ever since the 1990s, but didn't participate in the programs from China. Adoptions from Ethiopia show an uptick between 2008 and 2012. With 268 children adopted from abroad in 2013, Germany remains an insignificant player.

Australia

Australia received its first Korean adoptees in 1969, but those numbers remained only a handful until 1977. After that year they rose steadily until reaching its peak in 1987, when Australia adopted 306 Korean children.

Although we have no data for Australia before 2000, it is likely programs existed with the Philippines, India and Thailand as early as the 1980s. Those programs never provided many children so with the exception of Thailand, it is hard to say if they are in decline or if the numbers just fluctuate.

Most international adoptees in Australia come from Asian countries, with Ethiopia as a notable exception. Romania too was temporarily a source of children.

Australia started adoptions from China in 2000 and peaked in 2005. This is also the year Australia reached its high water mark, receiving 434 children in total. In 2013 that number had dropped to only 129.

The big picture

Looking at the data presented, some common patterns can be discerned. Before the 1970, inter-country adoption was relatively rare and mostly consisted of European children, predominantly from Germany, Austria and Greece. In the 1970s inter-country adoption picked up steam, headed by South Korea, that was responsible for most of the adoptions. During that decade nearly all programs in Asia, South- and Central America, and in Ethiopia started.

During the 1980s inter-country adoption mostly relied on programs from South Korea, Colombia, India, and to a lesser extent Brazil, Thailand, the Philippines and Haiti. Individual countries however had special relations with particular countries. Adoptions from Sri Lanka to the Netherlands and adoptions from Chile to Sweden are good examples.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsequent liberation of countries in Eastern Europe had a strong impact on some receiving countries, but not on others. There was hardly any noticeable effect on Sweden and the Netherlands, nor was there on Norway and Denmark, but it had a huge impact on the United States, France, Italy and Spain.

Children from Russia predominantly went to the United States, quickly followed by Spain, Italy, France and Germany, each peaking in different years. Children from Romania initially went to France and Italy, soon followed by the United States, Spain and to a lesser degree Germany. Children from Ukraine went to the United States, Italy, Spain, and to a lesser degree to France and Germany. Children from Kazakhstan went primarily to the United States and much later to some degree to Spain. While children from Bulgaria went in almost equal numbers to Italy, the United States, France and Spain.

Adoption from China since the early 1990s had a huge impact on almost all receiving countries, with Italy and Germany as notable exceptions. Both the ascent and the decline of adoptions from China happened more or less synchronously for all receiving countries.

The rise and fall of adoption from Guatemala was entirely an American phenomenon. While adoption from Guatemala surged in the US, it dropped in all other countries.

The rise and fall of Ethiopia is somewhat more complicated. France already placed a significant number children in the early 2000s and saw that number double in eight years time. The United States saw the numbers rise from 95 in 2000 to staggering 2,513 in 2010, while Spain raced from naught in 2001 to 722 children in 2010. Italy too went from almost nothing to 346 children in 2009, but manages to almost maintain that level to this day. Belgium, Canada and Denmark saw an uptick between 2007 and 2011, but not as pronounced. For the Netherlands adoption from Ethiopia was a long standing program that grew from three children in 1984 to 72 children in 2005, after which the numbers started to drop.

In recent years adoptions from Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana and Uganda have seen some increase. The numbers are not yet out of control, but there is cause for some concern. Especially the situation in Democratic Republic of the Congo causes misgivings with countries like the United States, Italy, France, the Netherlands, Canada and Belgium seeing the numbers increase in recent years, we may well have another boom bust cycle in front of us.

Conclusion

The picture presented of a decline in inter-country adoption since 2004, tells a very one-sided story. It egregiously omits the enormous increase of inter-country adoption in the period before the peak of 2004. This increase was caused by very special geopolitical conditions during the 1990s. Both the fall of the communism in the Eastern Bloc and China's decision to open its borders lead to a huge increase of children available for adoption. Those days are over and there is no reason to expect a sudden increase of inter-country adoption in the near future. In fact, there is reason to expect the decline to further continue. Most of the legacy programs from countries like Colombia, India, South Korea, the Philippines show a steady decline. Those programs are not likely to go away entirely. There is too much of a vested interest in those programs to make them completely disappear, but there is no reason to expect a sudden surge of adoptions from these countries either.

The only continent that has shown an increase in inter-country adoption in the last decade is Africa, where countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana and Uganda have started to send children abroad in significant numbers. Those numbers, however don't show the pattern of a boom, like seen in Ethiopia and Guatemala,. In part, this has to do with changing attitudes towards inter-country adoption. Much more is now known about child-trafficking and fraudulent adoption than a decade ago, but these countries also lack a long-standing adoption practice.

Both Ethiopia and Guatemala had adoption programs going back to the 1970s, enough time to build up a network of suppliers, lawyers and orphanages. Only when such a network is effectively in place, can inter-country adoption boom, and its those same networks that prolong a dependency on inter-country adoption long after humanitarian crises have been overcome.

Adoption from South Korea is the prime example of that phenomenon. Adoption from South Korea boomed in the 1980s, while the country was economically doing very well. There was no humanitarian reason to do adoptions from South Korea, but it continued and even increased out of social convenience and because it supplied an income to many involved.

To a lesser extent this can be said of all legacy programs, and the lesson we can learn from them is that once established, inter-country adoption only slowly fades away, even when the programs no longer serve a humanitarian purpose.

The future of inter-country is hard to predict. Humanitarian crises come and go, and major geopolitical shifts cannot be precluded. If however, the current world order remains more or less stable in the upcoming years, then inter-country adoption is likely to further decline. In countries like Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands, traditionally large receiving countries, inter-country adoption is likely to remain at low levels. France may show more ups and downs in the near future, and the same can be said for the United States and Canada.

The only receiving country that remains entirely unpredictable is Italy. Although a decline has set in after 2011, Italy has defied all patterns seen in other receiving countries in the years previously. It remains to be seen if Italy is just behind the curve and will continue to decline, just like other receiving countries, or whether Italy has diplomatic advantages over other countries allowing them to take in children that are otherwise unavailable.